Adam was seven years old when he discovered the secret to life.

He was in the corridor, practicing ‘bowling’ for this new fangled game called ‘cricket’, as children in the 1720s were wont to do. There was a satisfying smash as the ball connected with the porcelain vase he’d been aiming for. His elation was tempered only by the realisation that the ball had just connected with the porcelain vase he’d been aiming for.

He threw open the door to his mother’s room, to apologise, and she gasped as he burst in – as married women having carnal relations with the butler are wont to do.

Adam explained that it wasn’t him that broke the vase, it was an, erm, invisible hand. Fortunately for the young Master Smith Mrs Smith believed in poltergeists (spiritualism had experienced something of a resurrection in Western Europe), and she just wanted him out of her room, as mothers whose sons have just walked in on them having carnal relations with the butler are wont to do.

Adam was waved away without punishment.

As Adam grew up and moved to London, so did the invisible hand. Whenever he found himself in a tight spot, the translucent appendage would come into play. When a young ladyperson accused him of groping her on the shared carriage (with good reason, it must be said – he had), it proved to be an ample excuse. “It was not me, Officer,” Adam said, “It was an invisible hand what did it.” The policeman shook his head. The ladyperson tapped her foot. Adam scratched his elbow. The policeman shook the ladyperson’s head. Adam scratched the policeman’s foot. The ladyperson tapped the policeman’s head with her elbow.

They all continued with their lives.

When Adam attended poorly-catered dinner parties, an invisible hand overturned his bowl. When Adam was invited to a four-hour lecture on the origins and nature of the square in Lithuanian architecture, an invisible hand stole his ticket. When Adam smelt the floral overtones of a pleading charity worker, an invisible hand would slam the door. Then Adam would wonder if he had synaesthesia.

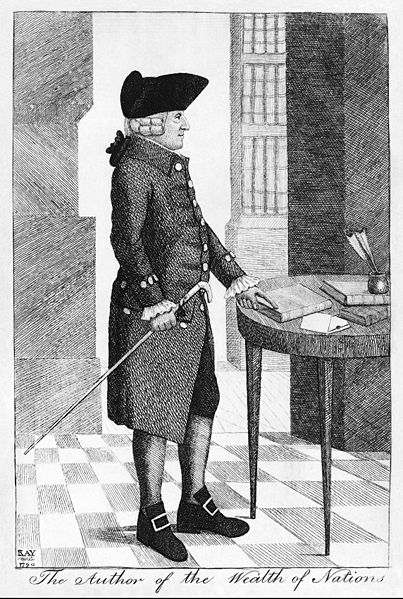

It was an obvious choice to write about the invisible hand once he graduated from university.

The moral of the story should be clear. If you ever find yourself with anything incriminating, or undesirable, or unfair, or Swedish, just blame it on an invisible hand.

It worked for Adam.

No comments:

Post a Comment